When it comes to muscle cars, 1970 is usually held as the peak year. There’s a small segment of the population that holds 1969 in highest regard, which is a valid counterpoint. But what if I submitted the idea that there was another year in the decade that was more significant for American automotive enthusiasts? As one who is familiar with a decade in which I did not live through, I respectfully submit 1964 as the greatest.

You don’t need to disguise your snickers—I don’t allow my feelings to be dictated by strangers—but you should hear me out.

Nineteen sixty-four was the year when everything converged. Glance at popular culture and you cannot ignore the Beatles as the band appeared on the Ed Sullivan Show in February of that year. It wasn’t just the Beatles that caught America’s fancy—a whole slew of bands tried to break into the American market, rendering the then-current crop of surf instrumentals and “girl groups” obsolete. This “British Invasion” spurred a batch of American kids to pick up instruments and learn to play, leading to innumerable bands that were formed in garages, some of which released 45s or even LPs as they matured.

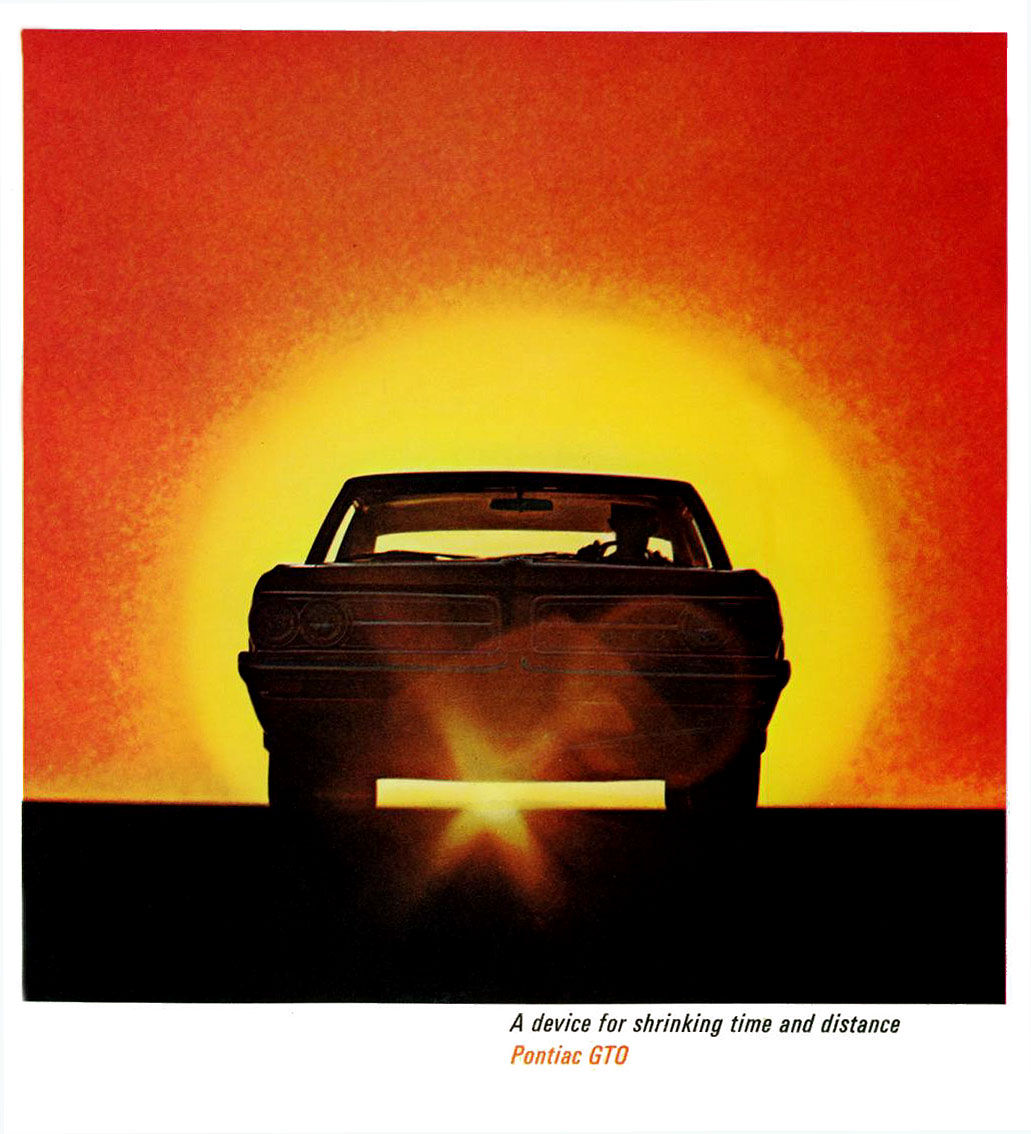

For Detroit, Pontiac introduced the GTO for 1964. The months leading up to the GTO were difficult for the brand because General Motors had ended all direct and indirect support for racing activities on January 24, 1963. This was to comply with the Automobile Manufacturers Association ban on racing involvement. Pontiac, a success in NASCAR and drag racing, had built its reputation on performance, yet now it was not allowed to do the performing. Pontiac’s answer to this was to focus on street performance and, with this paradigm shift, founds its way through an engineering experiment with a Tempest—newly upsized into a full-fledged mid-size vehicle. The top engine was planned to be a 326 High Output (which put out a respectable 280 horsepower), but engineers dropped in a 389 from the big cars for $#!+$ and giggles. After a bit of fun, they knew they had to get Pontiac to build this car but, alas, GM had an edict that limited cubic-inches to 330ci for mid-size vehicles. What made the GTO a brilliant move was that it was promoted through the upstairs offices as a package, which did not arouse the same scrutiny of approval as an actual model with an engine that was not allowed. By the time someone figured out the ruse, Pontiac already had several thousand orders for the car.

The GTO gave enthusiasts a nifty package that would end up influencing the whole industry.

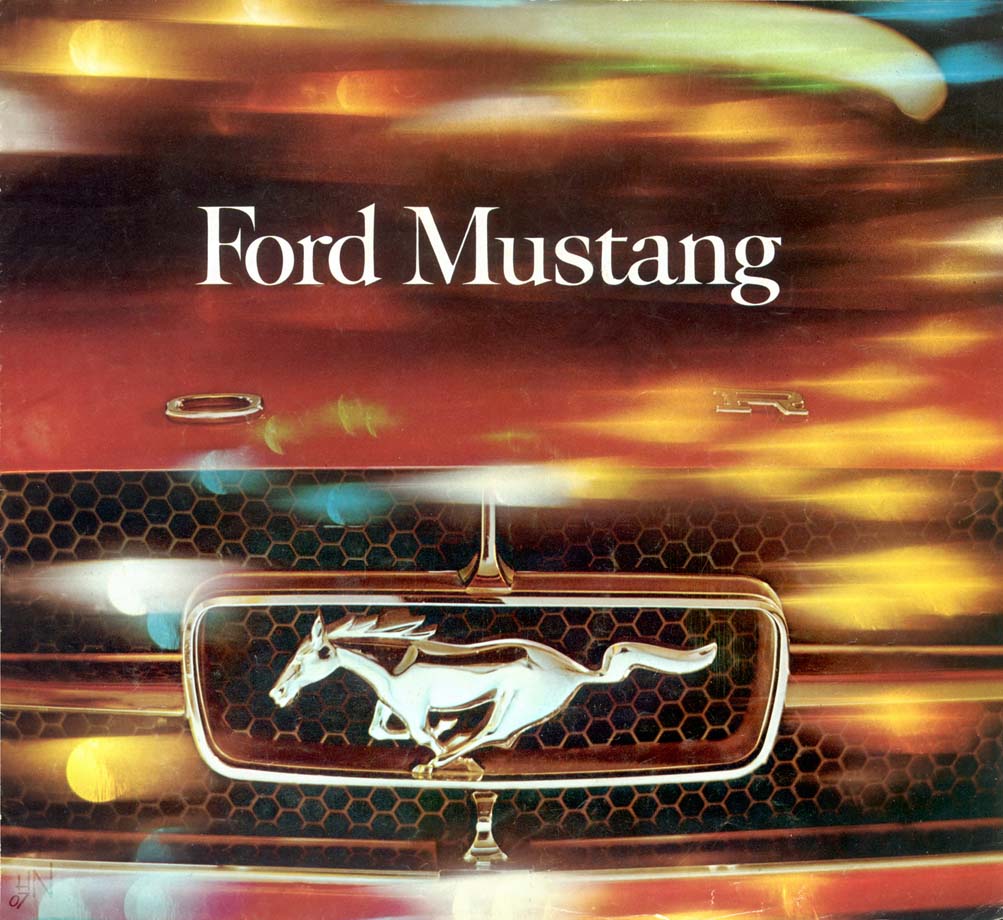

Culturally even more significant was the Ford Mustang, which was officially introduced on April 17, 1964. Though serially denigrated as a “secretary’s car,” the original Mustang was so much more: a car developed via market research—not unlike the Edsel—but with lessons learned. In a world where more households were buying a second car, the Mustang made sense; in a world where a large segment of the population was coming of age and ripe for driver’s licenses, the Mustang made sense; in a world where a new generation of youths was the largest generation in America, the Mustang made sense; in a world where more women were owning their own cars, the Mustang made sense. Sure, the Plymouth Barracuda debuted 16 days earlier, but it was not a marketing tour de force designed to capture the baby boom and other sociological elements—it merely was a fastback Valiant.

As you know, the Mustang captured the imagination of America, quickly becoming a phenomenon never seen in Detroit, and establishing a new class of American car.

Nothing in culture is a coincidence—several facets converged at the same time, one after the other. There is a reason 1964 rings strong and, as a result, it makes for a more substantive argument than any for 1969 or 1970.